Nothing protects us but our constant awareness and rededication to embody our values as much as we possibly can, and to be gentle with ourselves and others when we fail in this.

Author Archives: Shawndra Miller

Postcard from Hopland, CA

This weekend was the big Building Resilient Communities Convergence in Hopland, CA. I was excited to be there for part of the action.

A highlight was the mycology skillshare, during which Fungaia Farm‘s Levon Durr demonstrated several methods for home mushroom cultivation.

Teaching how to cultivate oyster mushrooms at home using the stem butt/cardboard technique to grow your own spawn. Sweet!

I didn’t know until recently that shrooms actually are a source of protein. This makes me even more determined to try cultivating my own.

I thought Levon was going to levitate when he got to the part about mycoremediation. His enthusiasm is not misplaced: Mushrooms can clean petroleum from drainage ditches and aid in riparian zone restoration. They even eat heavy metals and bacteria.

The practice of using fungi to clean our beleaguered earth of toxins is one of the most hopeful stories I’ve heard. It is also the subject of an upcoming guest post from Radical Mycology, so stay tuned.

Our Mailman Louis

From the neighborhood resilience files: Over on the Irvington Development Organization website, I recently guest blogged about our mailman Louis, who is absolute treasure.

Excerpt:

I think of Louis as a secret superhero ever since I heard that he tried to chase down a kid he caught kicking in a neighbor’s back door. I don’t know what color his tights are, or what exact powers he possesses, but I think he might keep his cape in that mailbag he carries.

Check out the IDO site to read the full post.

Garden Tower Update: Mistakes Were Made

Time for an update on our vertical gardening project. When last I posted about the Garden Tower, everything was growing robustly and looking smart.

I hate to say it, but that was kind of the high point of the season. The plants have not grown as vigorously as I’d hoped since that photo session.

Today there are five tomatoes just about ready to pick, but the plant looks pitiful. I cut off most of the grim stuff a few weeks ago.

Not sure what kind of maters these are; the plant was a sucker from a friend’s tomato patch, and she didn’t label it.

On the bright side, we’ve had several cucumbers, as well as snippings of basil, parsley, and kale. I’ve also harvested a few small beets from the top (with lovely greens)—and more are still growing.

The peppers have produced some sad little specimens, but then again we didn’t expect much, having planted them so late in the summer. I was excited to see peas and green beans, till I realized that the yield was going to be quite lean, barely a handful each. I guess one would need to plant almost a whole tower of legumes to get a “crop.”

Sadly the plants have just not grown very robustly. But the Tower setup isn’t to blame. My mistakes:

- I planted immediately after filling the barrel with the soil mixture. When I watered everything in, the soil sank a couple inches. This caused the plantings in the side holes to become quite leggy as they reached for sunlight. In retrospect, I probably should have watered well first, allowed everything to settle, and then planted. That might have given them a better start.

- I neglected to apply the weekly liquid fertilizer suggested by the literature that came with the barrel. Said literature was buried on my desk until recently. Oops. (After the first month this is supposed to be unnecessary as the worms do their work. But I imagine that fertilizing during those first crucial weeks would have given the plants a needed boost.)

- I overcrowded the side pockets, planting more than one seed. I told myself I would remove all but the strongest seedling later, and I did some thinning, but not nearly enough. I just didn’t have the heart to do it. I bet they would have grown bigger with less competition.

- I overfilled the center tube with veggie scraps at the very beginning: In my excitement over this new worm farming adventure, I filled it to the top instead of to the suggested one-third level. I don’t know if this was a factor or not. (We’ll see how it goes when we harvest worm castings!)

One point of pride: my daily hand picking of cabbage worms at the height of their infestation seems to have saved my kale plants. However, it was too late for the kohlrabi and cabbages, which have not progressed beyond seedling size. I’m told that an application of Bt and some ladybugs would eliminate these little munchers, so we’ll keep that in mind for next year.

It may have been another misstep to mix our compost into the potting soil, given how much trouble we’ve had with diseases in our tomato plants. I hated to see the tomato transplant succumb to the same yellowing and crispy leaves we’ve had the last several years in our regular beds. But: no blossom end rot; the tomatoes themselves are so far looking luscious.

We can’t do anything about the soil, short of dumping it out and starting over, and I’m not willing to do that. But the other issues are all learning points for the next growing season. With gardeners, it’s all about next year!

Difficulty

It’s something we all encounter in life; what do we do with it is what matters.

“Your difficulties are not obstacles on the path, they are the path.”

—Zen teacher Ezra Bayda

My Day at School

Yesterday I drove down to Bloomington to spend part of the day with my homeschooling coop friends. These two families use homesteading activities as the basis for their children’s learning, along with traditional math workbooks, writing assignments and the like.

The task of the morning was to prepare cedar limbs to build a spit for cookpots over a campfire. The previous week, the kids had cut branches off the cedar tree, with a goal of being able to climb it. They’d christened it Fort Cicada.

The brushy limbs now needed to be trimmed and the bark removed with a draw knife. The kids coached me on sawing. I can’t remember the last time I sawed something. It’s satisfying to cut right through a branch and have it fall.

The draw knife was a revelation. I have never experienced the pleasure of skinning a tree branch with a sharp instrument. I wasn’t sure I was qualified for the work, but the kids taught me well.

They assured me that they would use a regular knife to shave around the knots where the draw knife caught. Here’s the youngest, working with her knife.

I love how fearless these kids are. I find that my own hands are better suited to a keyboard than a hand tool. Yet, I pulled off a passable job on bark-peeling task.

After a while it was time for lunch (fresh-baked bread!) and conversation. I asked the four kids what life would be like if they went to a school where they sat at desks all day. They agreed that they wouldn’t have nearly as much fun and flexibility in their lives, and probably not be as fit. Nor would they spend as much time with their families. On the flip side, they have to schedule activities to connect with larger groups, whereas students in school interact with lots of different kids daily.

Asked how their education is preparing them for adulthood, they pointed to skills like gardening, cooking, and researching solutions to problems.

After lunch, it was time to split maple logs and stack wood for the winter’s fuel. This was more fun than I expected. I consider myself something of a pipsqueak—but seeing the kids demonstrate, I thought, why not try?

After numerous tries and tons of pointers from the peanut gallery, I managed to stick the splitting maul in the top of the log. I whapped at it with a mallet till the firewood split with a satisfying crack.

Alas, no one captured the moment on film, but I have the sore muscles to prove it.

All in all it was a great time with lovely people, and felt wonderful to be outside doing real work on a pristine fall day.

Drawing the Line

Saturday I took part in a local expression of a nationwide day of action, 350.org’s Draw the Line. About 40 of us came out to demonstrate resistance to the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

KI EcoCenter hosted the Indy event in partnership with Earth Charter Indiana. These two stellar groups both work at the intersection of environmental, social, and economic concerns.

Alvin, one of the organizers, started us off with a wholistic assessment of what we were about: creating a new world, beyond the issue of the pipeline or tar sands or even fossil fuels.

“Keystone XL is a symbol of the past…We’re saying no, we want something different for our world,” Alvin said.

In the ensuing discussion, there was talk of reining in corporate greed, making companies pay the true cost of production, reforming the way election campaigns are financed, and other policy changes.

But many people brought up the need for internal as well as external shifts. How are we making the old reality obsolete by creating a new reality, as Buckminster Fuller advised?

Some of the insights:

We need to build a united movement that encompasses social justice, because climate change disproportionately affects the poorest of the poor. —Rosemary

We have to shift away from the value we put on money. Companies value money and profits more than our own lives. We have to focus on the intangible side of life, such as happiness that comes from having a healthy place to live. —Keenan

The problem stems from the idea of separation—that we’re separate from each other, separate from the earth, separate from the animals. But we are one. —Marion

We need to change the definition of the good life. —Tom

We need to take responsibility for what we carry within so we don’t pollute the world with negativity. Anything inside us that fears and hates is that which is in common with what is feared. It’s important to notice—because when you notice things, they lose power. —Phoebe

At the end of the discussion, we lined up outside the center with signs we had made, and a KI EcoCenter intern drew a black line across to represent our line in the (tar) sands.

Though I much prefer creating the new world to protesting what needs to fall away, I do believe it’s important to stand up and be counted. I’m glad Indy was represented in the movement, however small our number. And we didn’t stand alone. These photos of the line’s reach (into hundreds of cities, drawn by thousands of activists) at 350.org’s flickr stream are inspiring.

Working with Nature to Sustain Life

There’s a fatal flaw in the traditional definition of sustainability—meeting today’s needs without jeopardizing future generations’ ability to meet their own needs.

The problem? This notion leaves out every species besides homo sapiens.

The truth is, “Human beings don’t sustain shit,” sustainability consultant Brandon Pitcher declares. “Nature sustains us. We fool ourselves into thinking we sustain the planet, but it’s the other way around.”

But Fritjof Capra’s view of sustainability is more integrated:

“A sustainable human community is designed in such a manner that its ways of life, technologies, and social institutions honor, support, and cooperate with nature’s inherent ability to sustain life.”

Pitcher, a certified practitioner of ZERI (Zero Emissions Research & Initiatives, a global network seeking solutions to world challenges), spoke at the Irvington Green Hour Tuesday night. He gave two scenarios of solutions patterned after nature’s wisdom.

The Power of Shrooms

The first involves using mushrooms to address multiple issues, such as in the case of an invasive species troubling poverty-stricken parts of Zimbabwe. There water hyacinths choke waterways, to the point that people can’t take their boats down the river, jeopardizing their livelihoods in an area already strained by high rates of HIV.

However, once harvested, dried, and sun-sterilized, this invasive species is ideal food for mushrooms. Villagers take the work on, and native mushrooms thrive on this biomass. Reintroducing mushrooms as a food source demonstrates how tasty and nutritious these powerhouses are—and they can provide enough protein to sustain a community in two to three weeks, Pitcher says.

Mushrooms also figure in food security efforts in Colombia, where the coffee plant forms a substrate for edible fungi. Typically 99.8 percent of coffee is thrown away or burned on its way to our morning cuppa. But “waste” is opportunity.

The Wisdom of Water

Pitcher’s second example is a natural way to treat wastewater.

In Indiana, 92 cities, including my hometown, have antiquated combined sewer overflows (CSOs).

Never heard of a CSO? You’re lucky. Here whenever it rains a fraction of an inch, raw sewage combines with stormwater runoff and runs straight into waterways. So pathogens and toxic chemicals are dumped into my neighborhood’s Pleasant Run and other sweet little streams.

The remediation plan involves drilling enormous pipes deep underground to hold the excess sewage. To Pitcher, this represents a wasted opportunity—and a sad ignorance about the way water naturally purifies.

“Water does not move in a straight line in nature,” he points out. Its natural flow creates vortexes that clean it. “It’s very ignorant of us to think we can move water through pipes in straight lines and think that water’s going to be healthy.”

An integrated system of rain gardens and wetlands harnesses the power of algae to treat wastewater. In Indy, such a system could have resulted in a decentralized network, providing jobs and clean water in perpetuity, Pitcher believes.

For more information, see the ZERI site, or The Blue Economy—or attend Pitcher’s upcoming sessions at Trade School Indy.

Indestructible

Here’s the mother of the modern environmental movement, on the importance of nurturing children’s connection with the natural world.

Boy scout photographing nature at the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge. Photo credit: USFWS, via flickr Commons

“If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children

I should ask that her gift to each child in the world

be a sense of wonder so indestructible

that it would last throughout life,

as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years,

the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial,

the alienation

from the sources of our strength.”

—Rachel Carson, The Sense of Wonder, 1956

My Dad, Who Made the World Better, Take 2

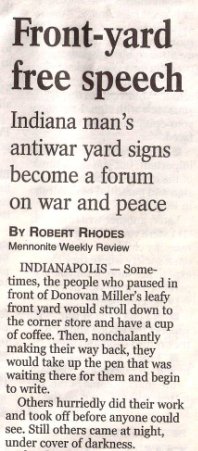

Recently I was going through some old files when I found a back issue of the Mennonite Weekly Review, with an article about my dad on the front page. Back in 2003, the periodical had taken notice of a “silent dialogue” he’d started about a controversial subject.

Recently I was going through some old files when I found a back issue of the Mennonite Weekly Review, with an article about my dad on the front page. Back in 2003, the periodical had taken notice of a “silent dialogue” he’d started about a controversial subject.

I remember it well. When his sign protesting the war met with surreptitious changes, altering its meaning, his response was characteristic of him as both a mental health worker and a Mennonite. Instead of shutting down, he sought more engagement.

In late winter of 2003, the US-led invasion of Iraq prompted Dad to place a sandwich board sign in the front yard. One side read “The Nations Say No to War” and the other said “The Whole World is Watching.” (Originally he’d worn this placard at a protest march.)

At some point that spring, someone took a pen to these antiwar sentiments, flipping the meaning with the addition of a few letters.

Dad didn’t get mad. Instead, he decided to invite passersby to participate in the commentary. He posted a blank sign, attached a permanent marker, and waited. The sign became an anonymous forum for the neighborhood to share a range of deep feelings about war.

Dad didn’t get mad. Instead, he decided to invite passersby to participate in the commentary. He posted a blank sign, attached a permanent marker, and waited. The sign became an anonymous forum for the neighborhood to share a range of deep feelings about war.

Back in the day, at Goshen College, we had the opinion board, where anyone could scribble their random two cents. Entertaining, enlightening, enraging at times, the content was a freewheeling snapshot of campus controversies and dilemmas. Dad’s more targeted opinion board showed the diverse positions among his neighbors: concern for slain children, desire to stand behind both military and government, gratitude for free speech, comparison to Vietnam, prayers for peace, and so on.

The safety of that anonymous pen reminds me a bit of today’s comment threads online, where faceless speakers can quickly turn meanspirited. For the most part in Dad’s case, the discussion was civil, though passions were clearly high. He posted a thank-you note after the white space was full to the edges, and took the sign down.

After he was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2011, he began to go through decades of accumulated belongings and papers. We searched for the yard signs in the basement, but they didn’t turn up, and I’m not sure there are any photographs. I was happy to find this somewhat crumpled record of his bridge-building efforts.

I lost a precious father and friend upon his death, and my family will never be the same. But this clipping reminds me that the wider community is also poorer for his absence.

I lost a precious father and friend upon his death, and my family will never be the same. But this clipping reminds me that the wider community is also poorer for his absence.