Monday morning a group of gardeners from the neighborhood had a private tour of Peaceful Grounds, Linda Proffitt’s endeavor at Marion County Fairgrounds, where the county fair is going on. (See my earlier post about her work here.) The vision and scope of this Global Peace Initiatives project astounded and inspired us.

George Marshall, Linda’s intern, showed us around the farm, where mounds of wood chips are not just regular old wood chips but worm habitat.

Peaceful Grounds takes beer mash from local brewers like Irvington’s own Black Acre and buries it in mulch to feed the herd of worms.

Hand-painted signs that say “Worms at Work” and “Thank a Worm” testify to the importance of these little red wigglers.

Volunteers mix 5 to 15 tons of mash with equal amounts of wood chips each week. Another mound incorporates dehydrated food waste from public hospital Eskenazi Health. Over time, these piles and rows are transformed into a viable medium for garden plants.

George showed us where vegetable and herb starts have been set right into these habitats.

Broccoli planted in one of many windrows made by worms doing their work on wood chips and beer mash.

In a nifty closing of the loop, Linda has begun to raise hops to supply local brewers.

While we were walking down the raised beds (“windrows”) of basil and tomatoes, a fair official came up and asked for Linda. He wanted to introduce her to the people in charge of an elephant exhibit, so she could incorporate elephant dung in the farm operation. (“You never met a lady more excited about poop than Linda,” George joked.)

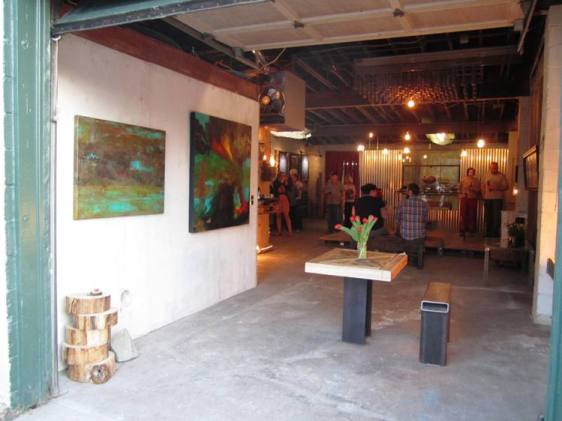

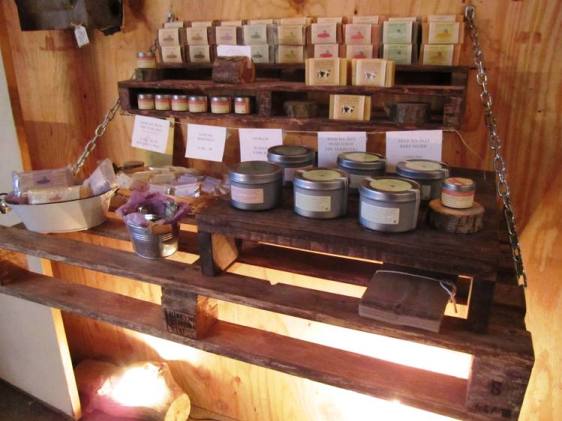

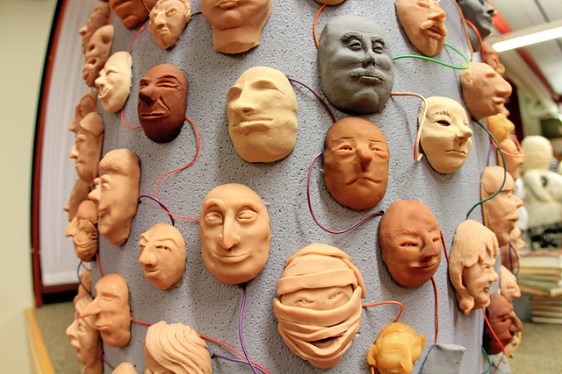

Inside the cattle barn is where kids and adults can come for hands-on fun with art and agriculture. It’s also where artists like Jamie Locke (another Irvington neighbor) demonstrate mandala making and other crafts—and where young volunteers from Handi-Capable Hands take charge of a gigantic tumbler that sifts the worm compost into two grades of product.

Heidi Unger took this photo of the tumbler, which is named Apollo and was donated by a local farmer who saw Linda on TV.

We went home with the finer grade, which is basically worm poo, to use as a powerful organic fertilizer. One tablespoon per plant will nourish it through a month, Linda says.

Before we left, we learned that Will Allen is going to visit the operation, which is a training outpost for his fabulous Growing Power organization. He will speak at 2pm Saturday and lead a workshop at 4pm, and will also preside over a ribbon cutting ceremony at noon on Sunday, when the Peaceful Grounds Farm and Arts Market kicks off.

I’d love to see more interaction between local urban gardeners and this facility, which is just a stone’s throw from Irvington’s back door. Right now the county fair is in full swing, but the possibilities extend beyond its closing date. Linda is running a Farm Camp for kids starting July 7, and is happy to host volunteers at any time.

I’d love to see more interaction between local urban gardeners and this facility, which is just a stone’s throw from Irvington’s back door. Right now the county fair is in full swing, but the possibilities extend beyond its closing date. Linda is running a Farm Camp for kids starting July 7, and is happy to host volunteers at any time.

By the way, she offered to set me up with an interview with Will Allen. I’m thrilled to meet this man I admire so much. I’m crowdsourcing interview questions. What would you ask the grandfather of urban gardening, if you could?