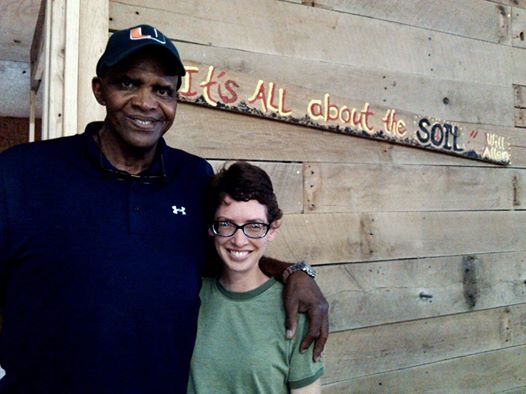

Last month I got to meet Justin Berg and Mike Higbee, who are doing something I admire: turning unused urban land into an agricultural oasis. As with many such endeavors, they glean local materials to build soil—leaves from curbside refuse, manure from the police department’s Mounted Patrol stables.

What’s unique about this urban farm, though, is that it’s being built atop the pulverized remains of an old mental institution.

To anyone growing up in Indy, as I did, “Central State” was synonymous with the loonybin. We all knew that it was an insane asylum, back in the day, and as late as 1994 it was still operating as a psychiatric facility.

The enormous campus fell into disuse after Central State Hospital closed, but recently the site has been redeveloped into Central Greens urban village. Part of the project includes Seven Steeples Farm, so-called because the 5-acre parcel being farmed is on the footprint of a building called Seven Steeples, where women were institutionalized.

The building was demolished midcentury, and apparently is now buried under the vast lawn area where Justin and Mike have begun growing produce for the past year. Sheltering old trees that must have borne witness to all kinds of pain still stand, shading the chicken run and outdoor classroom area.

I have to say, this thing has lit my imagination in surprising ways. I’ve read The Yellow Wallpaper and other stories of “madwomen in the attic.” How easy it was to cart women away for any infraction back when this asylum was established (1850s.) I can think of several reasons why I myself, in an earlier era, could have gotten myself tossed in there.

And what sort of “treatment” did the women undergo, inside the walls of Seven Steeples?

It feels to me like a major healing of an old wound to have an urban farm there. Community volunteers (and patrons) enjoy a peaceful setting smack in the middle of a somewhat sketchy part of town. The food is accessibly priced so that people living in the middle of a food desert can have a decent choice of nourishment.

Visitors love to sit on the stumps next to the chicken run and just get on “chicken time.”

The farm has announced 2015 CSA (community supported agriculture) plans, and will also have a weekly farm stand to sell eggs and produce. (More info: info@sevensteeplesfarm.com or 317-713-9263.)

Justin says, “Call to set up a tour, and everyone’s more than welcome to come by the farm stand if they’re in the area. They can grab up some produce and come check out what a rural setting could look like in the city.”

See my Farm Indiana piece for more on this project.