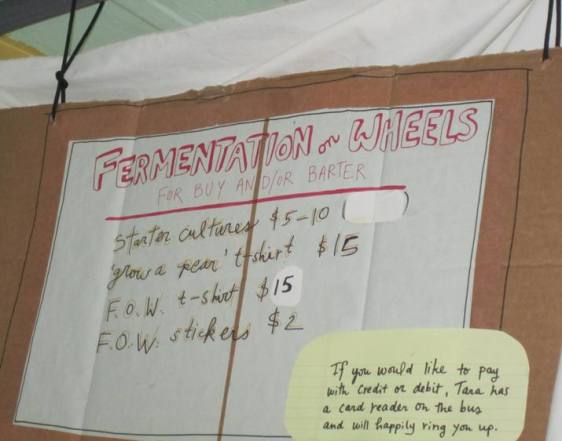

Fermentation on Wheels rolled into town over the weekend. Tara Whitsitt has been driving her mobile fermentation lab cross country since October 2013. As soon as I heard she was coming to Indy, I knew I had to make it to one of her events.

Fermentation on Wheels, a 1986 International Harvester school bus converted to a mobile fermentation lab

Tara’s mission is to initiate more people into the wonderful world of fermented foods (like sourdough breads, kefir, sauerkraut, wine, and kombucha). So far her tricked-out bus has traveled over 12,000 miles to share the love.

Saturday she did a fermentation workshop, which I hear was fabulous. Sunday evening, Seven Steeples Urban Farm (see my earlier blog post about them here) hosted a potluck and culture exchange. That’s where we met Tara and her beautiful kitty.

We had a terrific meal together that included loads of fermented drinks and veggies, some from the pros: Joshua Henson of Fermenti Artisan brought cultured ramps and daikon radishes, along with water kefir lemonade and a bunch of other delicious stuff. There was also a popular fermented drink called beer.

After we ate, it was time to check out the bus.

“I really want to spur the movement of getting back in the kitchen and doing things with our own hands instead of relying on other people to do it for us,” Tara told us.

All across the country, she’s been partnering with farmers and homesteaders to turn local harvests into something out-of-this-world delicious. People give her their home-canned peaches, for example, and bushels of chili peppers. She dried the chilis and used them in kim chee, and they are also a key ingredient in her peach-habanero mead.

We sampled kombucha, miso, and a mysterious drink of Tibetan origin called “jun.” (Instead of the black tea and sugar that make up kombucha, jun favors green tea and honey.)

We sniffed three types of sourdough starter, each with a different backstory. For example, the Alaskan sourdough came from a person in Portland whose great-grandmother had made it in the 1900s in Alaska. White flour and milk were the original ingredients, and that’s what Tara feeds it to this day. The starter is a key ingredient in creamy sourdough hotcakes favored by Alaskans.

No wonder she calls her starter cultures “heirloom” cultures: They’re completely different from something purchased online, typically made in laboratories.

Eating food from a starter passed down for generations is like wrapping your grandmother’s Afghan around you. Versus a Kmart coverlet. One is imbued with love and history. The other with factory threads and who-know-what labor injustice.

I wish I could say I had something terribly cool to swap with Tara, but she wasn’t all that keen on my dairy kefir grains (of unknown origin: a friend of a friend gave them to me). So, I purchased a rye starter that hails from Brooklyn. As we speak, I’ve got sourdough rye bread dough fermenting on the counter. I’m using Tara’s instructions and recipe: Fingers crossed!

I wish I could say I had something terribly cool to swap with Tara, but she wasn’t all that keen on my dairy kefir grains (of unknown origin: a friend of a friend gave them to me). So, I purchased a rye starter that hails from Brooklyn. As we speak, I’ve got sourdough rye bread dough fermenting on the counter. I’m using Tara’s instructions and recipe: Fingers crossed!